Distribution and System Robustness - Part 1

There exist a number of systems in the real world. Some of them are naturally formed, while some others are created by human beings. Important systems involve one or more research fields from a broad range as well as a long time span. Among the various properties of a system, a common one that draws attention from researchers in many fields is robustness. Robustness might be defined in very different ways in each field, but generally it means the ability to overcome failures resulting from internal or external events.

To better understand the concept of robustness and how / why a fault tolerant mechanism is implemented, we will walk through several examples to explore their analogies, starting from distributions in IT systems. We will delve into other fields in Part 2.

IT

Almost every system has incorporated some degree of robustness. Generally there are many kinds of failures in IT systems, such as disk failures, OS crashes, application crashes and network link failures. Different systems are faced with a different set of major failures to cope with, as well as different patterns and probability distributions. Let’s examine some of them and their corresponding solutions, while not restricting ourselves to only robustness itself but other aspects of a system.

Operating systems

For OSes, the failure may come from any of the following hardware components:

- CPU

- Main memory

- Disk

- Other I/O related hardware

The failure might be caused by hardware itself or the OS software that manipulates it. In general, it is relatively rare for hardware errors to occur, since they’re carefully designed by engineers for a high cost to fix any potential bug. But these errors do happen sometimes. In addition, OS software themselves crashes a lot, especially drivers of I/O devices.

What makes things worse is that power failures or natural disasters would stop CPU and volatile memory working immediately. Taking the above events into account, we have to turn to disks to keep any valuable data persistent.

While some major operating systems (including Linux) took the design philosophy of monolithic systems, others preferred a different approach. One of them is named microkernel, which explicitly divides the components of OS by functionality and runs as few components as possible in kernel space. The major advantage is that in the event of a user space component failure, the kernel part can automatically restart or replace it and avoid total system crashes. As most of the functions are distributed to OS components residing in user space, it would be less likely for the kernel to crash and easier to isolate crashed services. There would be less exploitable OS vulnerabilities as well. One of the trade-offs is the affected performance due to communication overhead between components.

RAID

Disks (including hard disks and SSDs) are crucial for they’re the only online non-volatile storage. Whenever an unrecoverable system crash is triggered, disks play an important role in restoring the system state after restarted. However, disks themselves may well fail too (though much less frequent compared with software failures). Moreover, the probability of disk failure grows fast after using it for several years. Thus there is a motivation to provide further robustness even in the event of disk failures.

RAID (Redundant array of independent / inexpensive disks) is such a technology that can help to lower the possibility of unrecoverable disk failures. The key idea is to replicate the disk data and use the redundancy to recover from certain kinds of disk failures. Various RAID mechanisms and their variants exist, and they emphasize different degrees of fault tolerance, I/O performance and redundancy costs.

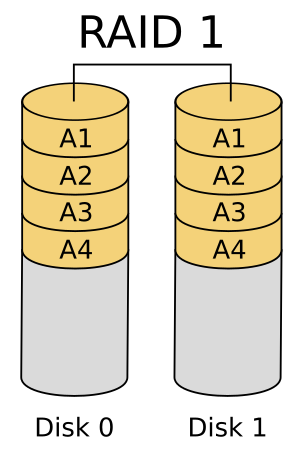

Among them RAID 1 and RAID 5 deserve special attention. RAID 1 employs full mirrors of original data; that is, two replicas of data are maintained at the same time in the disk array, and data consistency is ensured by stable writes. RAID 5 adopts a less costly method which adds an additional parity bit for every corresponding group of bits in other disks of the array.

RAID 1 and RAID 5 can resist failures of at most one disk. For further storage reliability, we can either add more copies of data or additional parity bits. However, the increasing storage cost (especially RAID 1) and the extremely low possibility of double or more disk failures result in the wide use of RAID 1 / 5.

Networks

Public Internet is unstable in many aspects. In particular, there is no guarantee for message delay, which means that a message can arrive in the indefinite future in theory even though TCP provides a reliable data transfer service, in case that there is no available connecting link or routers between hosts. Before we address this problem, we first look at the network topologies.

Network topology and hierarchy

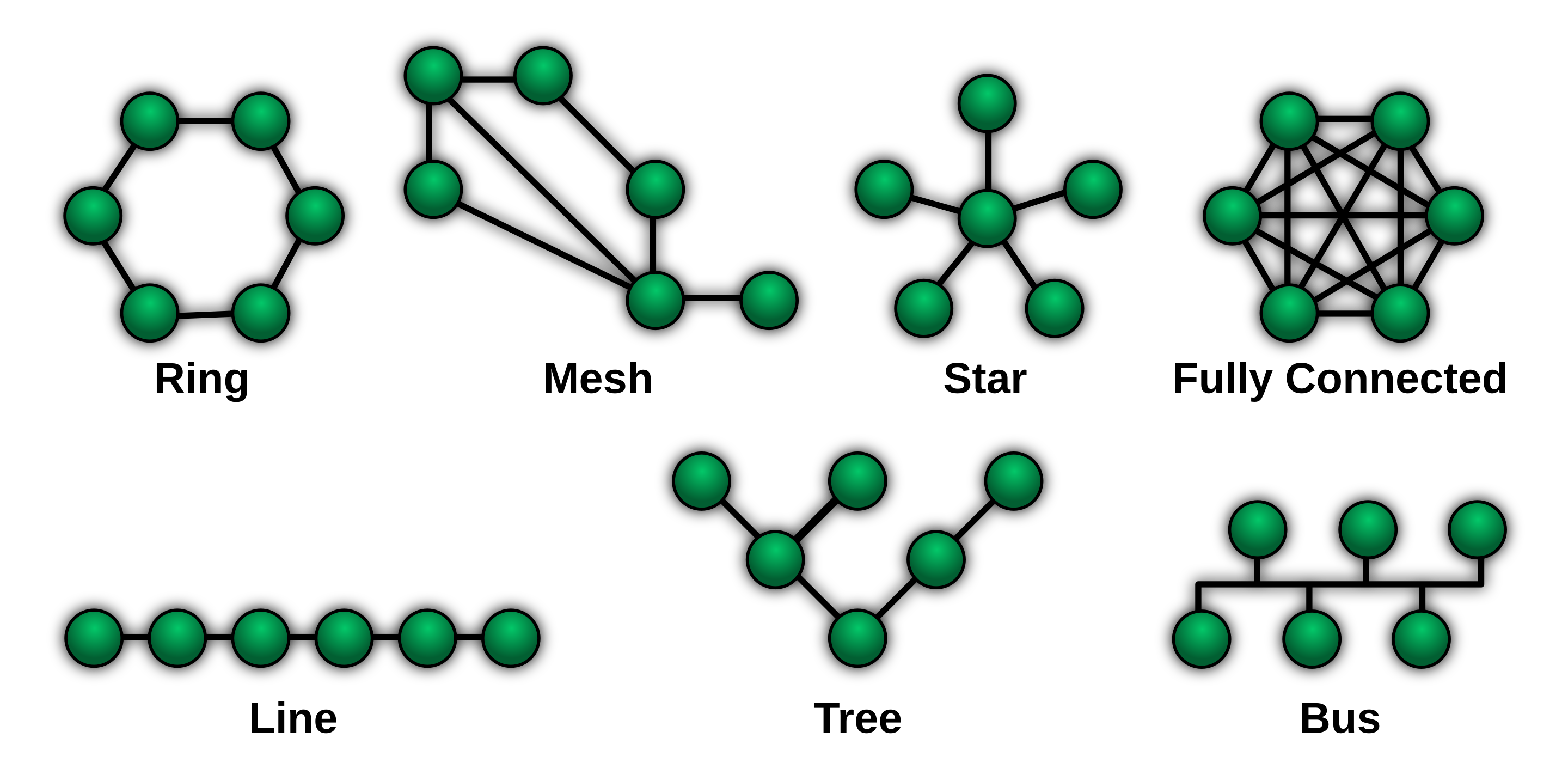

There are several common network topologies as following:

We concentrate on the analysis of the aspect of robustness. Generally the more interconnecting links, the better fault tolerance and the higher cost. If our Internet relied on a single specific packet switch to forward most data, its failure would cause severe shut-downs of the entire network. In fact, the real topology of the Internet is approximately hierarchical with many extra interconnections besides the links between direct parent and child nodes, which guarantees resistance to single point of failure of routers or links to some degree.

Data center network design

Analogous to the public Internet, we need to design a highly scalable and available network for data centers, where thousands to hundreds of thousands machines reside together.

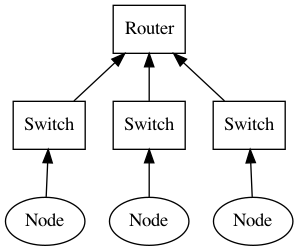

A trivial hierarchical design to organize computers (represented as Node) is as below:

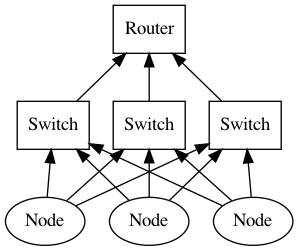

Consider the bottom nodes containing multiple machines. Obviously, it suffers from a single point of failure of a single parent switch. The alternative design can add redundant links:

Not only the failure of a single switch is prevented, but it potentially improves the throughput of inter-node data exchange. Of course the real topology of a data center network is much more complicated, but we should have made the basic idea of scaling such a network while providing a high degree of reliability.

Beyond failures

Recently Apple announced a new planned feature named private relay, which offers a 2-hop proxy service. It is reminiscent of the classical 3-hop design of the famous Tor network. One of the fundamental differences is that Apple and its another third party proxy provider can be trusted to some degree, while Tor network consists of totally unreliable and trustless nodes provided by volunteers across the world.

It’s much more challenging to build an anonymous distributed network on a layer of failure prone or even malicious nodes. One of the key ideas is that traffic proxy functionality is distributed over three random distinct nodes. Client first constructs a virtual circuit, choosing three nodes as relay servers in order and negotiating encryption keys with them individually. After it has been successfully constructed, any traffic can be relayed through these nodes, and only the exit node is exposed to the destination website. Note that the entry node knows who you are but not your traffic; the exit node might know the traffic but not who you are. A random intermediate node further rules out potential collusion between entry node and exit node.

In addition, every 10 minutes the circuit will be reconstructed so that no single relay could intercept the whole traffic.

Distributed data storage

A major motivation for distributed data storage is fault tolerance against single point of failure. There are a large number of data storage systems with diverse characteristics and purposes.

For example, it’s almost required to guard against failures of a minority of machines which may otherwise render a service completely unavailable. To further extents, a single spot where servers reside in a centralized manner is potentially vulnerable to power failures or natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes). Thus there are enough reasons to replicate data in another geographic region.

On the other hand, while centralized servers may enjoy low-latency and high-throughput internal interconnections, links between geographically distributed replicas present a significant degradation because of the intrinsic characteristics of public Internet. Worse communication conditions, or even network partitions, then obstruct the efforts to maintain data consistency. It should be comprehensively evaluated along with specific application demands to settle on an acceptable trade-off.

A basic idea to maintenance of data consistency as well as some degree of fault tolerance is to use a majority mechanism to ensure that every participant node would learn the same final data eventually, even in the event of machine or link failures as long as majority of them are active and connected. Such a decision making process can be formulated as consensus algorithms. As a common example, the famous 2PC (two-phase commit) protocol for parallel databases has an undesirable property of blocking on the failed coordinator. Using consensus algorithms to reach an agreement between a group of nodes coordinating other participants can help to avoid such a blocking problem.

Sometimes we need more availability even when the majority requirement cannot be achieved (like multiple network partitions). Some systems weigh consistency more than availability, whereas other systems can tolerate some degree of such data consistency and merge them later.

Fully distributed schemes

Most data storage demands occur in a single organization. Hence this organization takes complete control of its data and machines. Distribution schemes are generally designed to elect a master node / coordinator to manage requests, responding efficiently while robust to failures to some extent. However, there are situations where better reliability is required, or there may not be a centralized administrator at all.

One of such distributed designs is DHT (distributed hash table). Different from the hash tables, DHTs are not mainly used for compact storage of wide-range keys and efficient operations on them. Instead, DHTs are rather deployed as distributed routing services supporting point look-ups.

Suppose multiple keys are partitioned on a large number of machines. In a naive scheme, a client needs to query all of them to get the desired key in the worst case, which may well result in request flooding if there are a plethora of machines and clients requests. Building a single directory / routing table is infeasible as well, since such a table is too large to fit into main memory if there is a prohibitively large number of entries. In the case that no central organization exists, the administration work makes centralized control even more complex.

DHTs, on the contrary, does not require a centralized authoritative node at all. Routing information is distributed over the entire set of nodes in the network, and only a reasonable space is needed to answer queries in reasonable time.

For example, consistent hashing is a DHT technique supporting $O(\log n)$ look-up while using $O(\log n)$ space, which allows reasonable performance even on a large scale. We can imagine the keys are distributed over virtual nodes on a circle, and virtual nodes are mapped to real machines. Intuitively, each virtual node should store more routing information for its nearest neighboring nodes, while less for “distant” ones. Such distance can be defined in any appropriate way indeed if it conforms to the topology of the overlay network. The distance between search keys and virtual nodes is used to determine on which node the key should be stored. In the case of consistent hashing, keys are stored in the nearest virtual node clockwise.

Nodes can enter or leave the network at their discretion without any disruption to the service by collecting or distributing search keys from / to other nodes. Keys themselves are replicated over multiple machines. Thus, a single point of failure won’t damage the availability of service, even in the event of machine failures or network partitions on a large scale, as long as the system is distributive enough. BitTorrent is a file-sharing protocol such that many of its clients support DHT file queries, while IPFS is a distributed file system fully decentralized on a global scale.

It’s worth mentioning that those reliability gains are not free. Even for $O(\log n)$ look-ups in theory, such operations suffer from significantly more message exchanges and network communication. As a result, network delay and bandwidth limit place strict constraints on the application of DHTs, particularly in the public Internet. Also, only point look-ups are supported by DHTs (just like native hash tables), therefore it’s not suitable for range queries, which could trigger an excessively large amount of look-up traffic.

Malicious attacks, revisited

Just like potential malicious nodes in Tor network, we could be faced with such nodes in distributed data storage services as well, especially in the public Internet. Attackers could launch Sybil attacks against such systems, controlling a large number of nodes and imposing substantial influence on the system.

Although there is not really a perfect solution to it, there do exist some mitigation measures. For one thing, Sybil attacks arise from the overwhelming quantity of malicious nodes, so simply considering more nodes when processing a query would work. A random selection of nodes for consideration also limits the possibility that malicious nodes could do constant harm, as a random pick of routing path in Tor.

There is a set of consensus algorithms designed under the assumption of the trustlessness of a minority of nodes. Such algorithms are called Byzantine algorithms. Participants can achieve agreements even when some of them behave adversarially.