Transport Layer: Multiplexing and Demultiplexing

The Internet has been an important infrastructure for our society since the invention of Web. Nowadays, a huge traffic is flowing through the global network, supporting innumerable applications and services running on it. If one is somewhat familiar with the underlying architecture, he/she would probably hear of terms like IP, TCP, UDP and so on. Especially for some programmers, they would typically deal with TCP/UDP ports in their everyday work in the process of service development. Ports may sound trivial since it’s so basic and simple a concept. But have you ever thought about why there should be such ports?

Before this discussion, let’s begin with a general introduction to the Internet architecture.

Background: Internet Layered Architecture

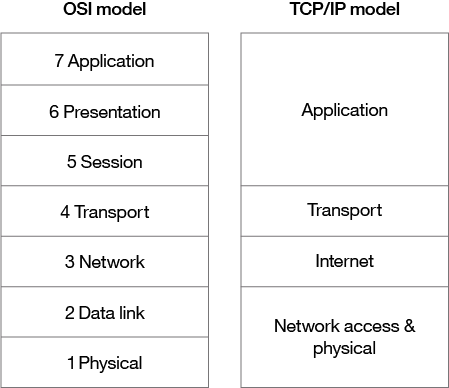

Generally the Internet can be described in the following layered stack.

Note that there may be several possible divisions in different granularity. In the figure above, we see that in so-called OSI model there’re seven layers, while in another possible division only four exist. In practice, the previous one does not make sense in dividing in a more fine-grained way. (In fact there’s no actual modern network operating under this model!) So we adopt the latter one (with simpler four layers) for our further discussion.

Application layer, as its name, is responsible for the communication between entities running a specific application. The best-known application layer protocol is HTTP, which forms the foundation of the modern Web. Other applications like emails are also served by this layer. Almost every application that you use on a daily basis with Internet access is directly based on application layer for network communication.

While application layer is heavily used for application-specific communication, the message formats and semantics are often defined separately. Many services share a common demand to deliver something from A to B. To avoid a repeated or even impossible individual effort to achieve the functionality, we may consider extracting the delivery as a common service. As an analogy, power plants are shared by hundreds of thousands of families in an urban area, instead of requiring each and every family to build their own generators. This is exactly what transport layer and Internet (network) layer do.

Note that we would use network layer to refer to the second layer. Internet is perhaps the largest network (of networks) so far, but many other networks may well exist without connection to Internet and use their own network protocols.

The lowest layer (namely, network access/data link and physical layer) is mostly implemented in hardware. As it’s not adjacent to transport layer, it does not interact with transport layer directly. For simplicity, we will give it a minor treatment and focus on our topic.

Demand for Remote Communication

For processes located on the same host, their communication falls into traditional IPC (Inter-Process Communication). The ability to network individual machines spurred demand for communications between different hosts.

IPC

IPC is the traditional communication between processes on the same machine. Generally, IPC provide a synchranization mechanism for processes in order to coordinate or compete with each other while sharing some common resources (e.g., memory, state, message, etc.), which results from interrelated processes.

IPC mechanism on a local host is dependent on the specific OS. For example, UNIX systems support pipes (byte streams between processes), signals (indication of some event and subsequent actions), memory sharing and so on. They’re implemented in different ways on different OSes. Pipes are typically represented in the form of files. IPC between threads are similar to processes, and there’re also some subtle and important differences. But those differences won’t bother us with our discussion.

File and File Descriptor

Processes are able to open, read and write files. To access the files on disk, processes need to maintain some critical information and state for currently open files, such as identifiers for files, identifiers for files in a process (a single file can simultaneously open in multiple processes) and current position pointer in a file.

Operating system is responsible for maintaining those information, and for user process to perform a limited set of operations on a file, a file descriptor is passed to user process as an identifier for the file in this process. We invoke library functions to make system calls through OS and read/write the file. To a user process, the file descriptor serves as a representation for some file.

Although files are usually mentioned in the context of data access on disk, a file does not necessarily manifest itself in external storage medium. Since files have to be mapped into memory to either read or write before writing them back, what processes actual operate on is a copy in memory. In other words, processes are unaware of whether the file exists on a hard drive, because the only visible thing is a region of memory. It has the consequence that OS can maintain memory-only files which look the same to processes as normal files.

Need for Remote IPC

It’s certainly crucial to find some way to deliver data from one host to another. But the path is yet incomplete. Applications run in the form of processes, therefore in case that two applications on separate hosts wish to communicate with each other, there should be a mechanism to achieve process-to-process level communication in addition to host-to-host, as many processes might run on the same host and want to communicate with others as well.

Astute readers may see that it’s possible to combine the process-to-process and host-to-host transfer and implement them in a whole in which each process has its own host-to-host connection. In essence it’s well feasible and was once designed as such in history. But we will have a look why the Internet decouples them in the final sections. For now let us assume host-to-host data transfer through public Internet is a separate service (i.e., Internet/network layer) and we’re trying to distribute the data from host to each process.

Multiplexing & Demultiplexing

In computer networks’ terminology, multiplexing between transport layer and network layer is collecting data from processes and send them through the common host-to-host datagram transfer infrastructure, while demultiplexing on the receiving side is distributing datagrams received by a host to the individual processes.

Socket: Remote IPC Interface

As mentioned above, each process should have an interface to send its data into network (multiplexing) as well as to receive those data destined for itself (demultiplexing). Sockets do exactly this.

Suppose a postman has filled your mailbox with plenty of letters. How would you distribute the letters to your family members? Definitely by (first) names. Here the postal address of your house is analogous to a network address for host-to-host data transfer (imagine your house as a host), and the recipient’s name is an identifier to demultiplex letters to specific persons. Similarly, a port is used to identify the destination process for an arriving datagram.

A simpler model is to use the identifier of process (i.e., PID) to distinguish differently destined datagrams. However, it might be well possible that multiple processes on several other hosts are contacting the same process on the local host. Thus, for a many-to-many mapping, it’s better to decouple them and allocate a distinct identifier.

Now that we have the port, it’s natural to create such an interface associated with ports. Consider a typical host with only one network IP address bound to a single network interface. (This interface is not a transport-layer one!) Assume there’re multiple datagrams destined to some process on the host. To distinguish them, we can first add so-called port identifiers to the datagrams, and then maintain a table in OS kernel mapping ports to processes. Ports should hold OS-wise uniqueness globally. As such, a port can only be exclusively possessed and used by a single process.

Basically, we can bind the (destination IP address, destination port) pair to an interface for user processes. The interface is called a socket.

UDP Header Format

Recall that the port identifier should also be appended to the datagram. Since we are talking about a transport layer service on the basis of a network layer datagram, it means an extra protocol and corresponding packet format is needed to record this information. The following protocol, called UDP (User Datagram Protocol), is aimed at it.

- Destination port: This is exactly what we need to demultiplex datagrams to specific processes. Note that the port is a 16-bit integer, limiting the available range of port numbers to $[0, 2^{16}-1]$

- Source port: Readers may ask why a source port is recorded here. Sometimes the receiver may want to send a reply (e.g., “I’ve got your message!”), so the receiver also wants the sender’s port

- Length: The sum of length of the header (8 bytes) and payload, used when extracting UDP packet as the length of payload is variable

- Checksum: Error detection against bit flips

Implementation

Armed with the abstraction of socket and UDP protocol, we are on our way to the final step to implement a socket. Sockets, along with their bound port numbers, serve as an interface for communication between processes. It should be reminiscent of the formerly mentioned IPC, which is also targeted at giving a synchronization and communication mechanism (but on a local host). On the other hand, the implementation would be better if it can reuse existing IPC infrastructure, which could in turn provide a unified interface for both IPC and remote communication.

Therefore, in UNIX systems sockets are implemented in exactly the same way as pipes (that is, represented as files). To send UDP packets, we write to the socket file; and to receive UDP packets, we read from the file. In this way, OS organizes network communication, local IPC and normal file read/write as if they were the same. What a clean and elegant design!

Connection-oriented Transport Layer Protocols

So far we have restricted our discussion to a simplest data transfer paradigm. One host send UDP packets, and the other receive them. If the network is reliable and stable without any loss, corruption or reordering of packets, we would be happy with this scheme. However, in reality the network is free from none of the above, making it difficult to create application like file transfering based on UDP.

One solution for the Internet is another reliable data transfer protocol, TCP (Transmission Control Protocol). It’s a connection-oriented protocol while UDP is connection-less. That is, TCP maintains the information and state of the connection between sending and receiving sides.

We intentionally ignore TCP because it’s somewhat more complicated with regard to multiplexing and demultiplexing. A quadruple of (source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port) is required to distribute TCP packets now. We may introduce it later in successive articles, but the fundamental idea is consistent.

Similar Designs in IP and Link Layer Protocols

Let’s conclude this section with a broader view of other layers in the protocol stack. We just described how UDP packets are distributed to processes. But as we may notice, UDP itself is not the only choice of transport layer, with possible rivals such as TCP. Both UDP and TCP can well do their own business, but how do the network layer know to which protocol it should hand over a specific datagram?

Interestingly, the header of IP protocol contains a field named Protocol indicating to which transport layer protocol it should forward a datagram. For example, UDP is identified by protocol number 17.

IP is sometimes known as the narrow waist of protocol stack, because there is no major substitute for IP in network layer and IP is a de facto standard in public Internet infrastructure deployment, which glues together individual networks, whereas there’re multiple transport layer candidates and link layer candidates. Note that in theory network layer functionality can be embodied in any satisfactory network protocol. So the possibility that link layer has to demultiplex to different network protocols does exist. This is done in a similar way in link layer frame headers.

Architecture Design Issues

We’ve walked through the multiplexing and demultiplexing functionality of transport layer protocols up to now. But there’s still a remaining issue that we put forward previously: why the network layer is separated from the transport layer by design?

Transport Layer vs. Network Layer

One would naturally ask why it’s necessary to divide the two different but tightly tangled layers. It can possibly be much simpler if it’s treated as a monolithic whole. Say we have another protocol that combined the functionality of host-to-host and process-to-process data transfer. Will life be better in this way?

Let’s review the services provided by each layer. Network layer is deemed to deliver a packet from one host to another across the public Internet, while transport layer is made on top of network layer, utilizing the services provided by network layer lying right below, and collecting from and distributing to different processes their destined packets.

In fact, the aforementioned TCP provide more services than the simplest demultiplexing: reliable data transfer, congestion control, security services (confidentiality, data integrity, server authenticity) via TLS, etc. It’s the transport layer’s freedom to choose what services it’s going to provide for upper layers. Except for TCP and UDP, there’re also a lot of other transport protocols, aiming at different set of services. If they’re combined with network layer protocols, then we have to implement the network layer part one by one. It’s no doubt a waste of resources.

In addition, thanks to the unified IP infrastructure deloyment, we can run various transport layer protocols on the end system without modification to routers, NAT devices and other IP-related hardware in the network core. If there’re tens or hundreds of network layer protocols rivaling each other, it would be much more costly or even impossible to internetwork the heterogeneous networks. The simplicity and universality of IP enabled the emergence of Internet.

From the perspective of microeconomics, the absolute majority of IP-conformant devices makes it a reality to produce them at a low marginal cost benefitting from economies of scale and entails the proliferation of those devices as commodities, which contribute a lot to the quick expansion of Internet.

History: NCP and TCP/IP

The predecessor of the modern Internet, ARPANET, was originated in the 1960s sponsored by ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency, now DARPA) of U.S. Department of Defense. In its early days, NCP was run as both a modern transport layer and network layer, which essentially governed process-to-process reliable data transfer combined with network layer functionality.

Some researchers had recognized the necessity of a general protocol to interconnect university, government, large corporate and other networks at that time, which resulted in the initial TCP/IP protocol. It was at first a single entity, but later split into two separate protocols operating on different layers. TCP/IP replaced NCP in ARPANET in the 1980s and from then on forms the cornerstone of Internet.

Conclusion and Distilled Principles

Now we can complete our discussion with a summary. Network layer is responsible for host-to-host delivery, while transport layer is responsible for process-to-process communication based on network layer. One of the basic (and most important) functionality of transport layer is multiplexing and demultiplexing. UDP is an exact example achieving this simple purpose. For the simplicity of IP and UDP, they are often used as infrastructure to implement higher level functionality in a more customized and flexible way.

Transport layer invokes the service of network layer, and at the same time provide services to upper application layer. This layered architecture proves extremely successful in the modern Internet, giving rise to a number of popular applications running on top of TCP and UDP. A modularized design helps to decompose a complex system like the Internet into several components that are relatively easier to engineer, manage and maintain.

IP, the narrow waist of Internet hourglass, is kept simple and stupid and dedicated to the most challenging task to deliver datagrams across the complex topology of Internet. On the other hand, transport layer protocols extends its functions and provide further flexibility, convenience and easy to use interfaces to user applications programmers. From the design and abstraction of transport layer, we should be able to learn a lot that can thus inspire us to apply to general system design.